We start going up a staircase in one of the buildings of the complex. I couldn’t quite remember how many flights there were, for I was too excited about where we were headed. I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but we just took the same steps that Charles Vermot took many times over, in the decades gone, to save the El Primero movement. This was a pilgrimage to the site where one man’s convictions, rebellion and sheer will shaped the future of Swiss watchmaking. We were on our way, up towards “the attic”.

The Summer of ‘69

The year was 1969 and what a time to be alive. The legend of Woodstock was born, John Lennon & Yoko Ono staged their “bed-in” and Sesame Street premiered. Concorde just took its first test flight whilst the Boeing 747 started its commercial service. Further out of course, man landed on the Moon.

But things were hotting up in the horological world back on Earth, the race for the first automatic chronograph movement was about coming to a head. On the Swiss front was Zenith with the El Primero vs. a group composed of Heuer, Breitling, Hamilton-Buren & Dubois-Depraz with the Chronomatic line. In the Far East, Seiko was working away with its Calibre 6139.

The winner of this automatic chronograph race is the stuff of endless debate with each one having a claim depending on how the race is defined. However, despite the introduction of these mechanical marvels, something else later that year was about to be the progenitor of a technological advancement that causes a crisis, or a revolution depending on which side of the upheaval you were on. In December 1969, Seiko released its first commercial quartz watch, the Astron. It would start a ripple that would change the horological landscape in dramatic ways.

It’s the end of the world as we know it

The 70s saw a wave of quartz models come into the market. Seiko was joined by the likes of Bulova, IWC, Longines, Piaget, and Rado in the adoption of quartz movements. Even the likes of Rolex, Omega and Patek Phillipe were in on the action. For some, the winds of progress, so to speak, was not very kind.

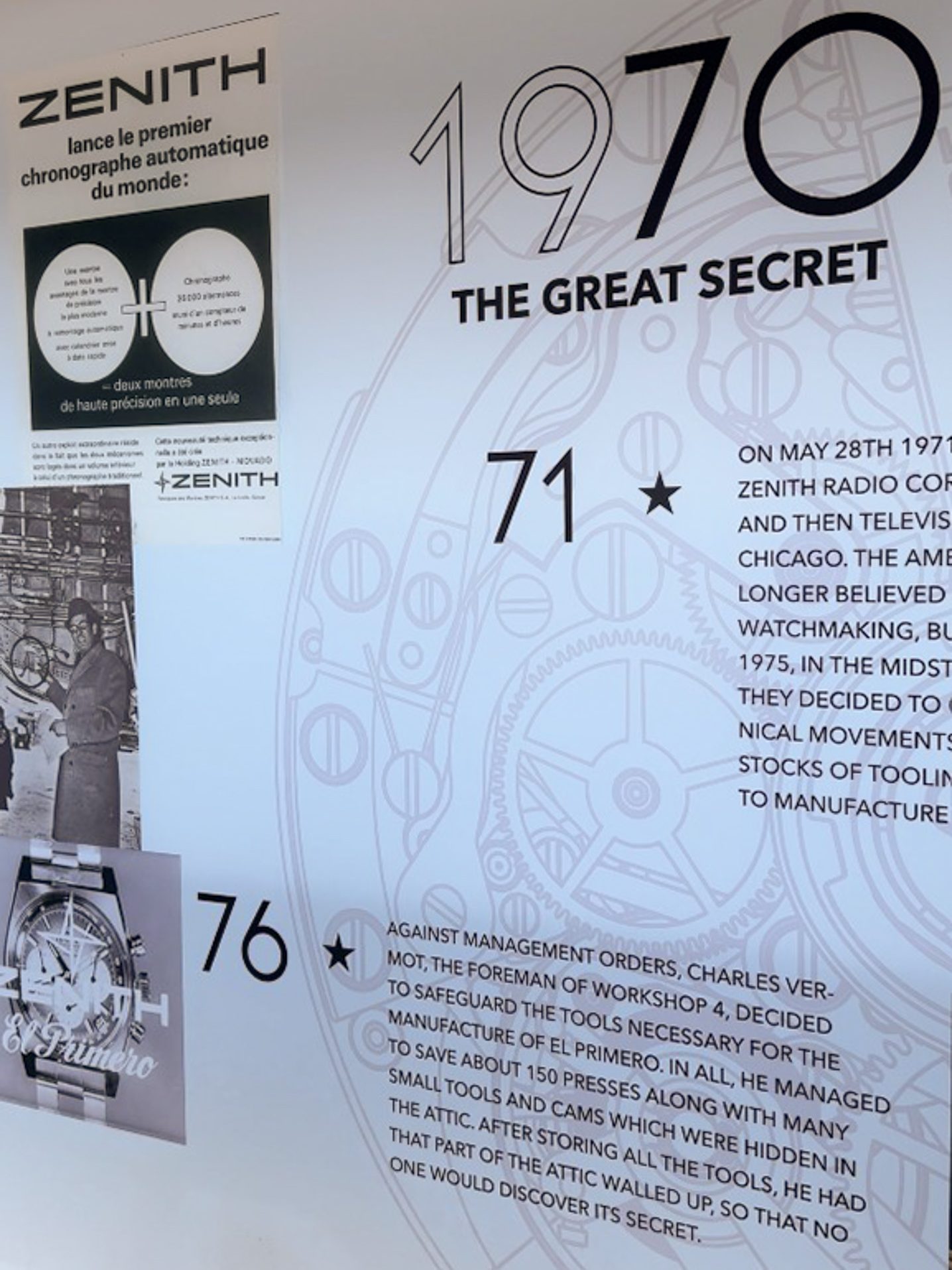

In 1971, Zenith Watches was acquired by Zenith Radio Corporation, keen to get into the watchmaking industry. Being an electronics company, however, it was eager to ride the hype surrounding the production of quartz watches.

Whilst Zenith was part of the consortium behind the Swiss Beta21 quartz movement, it still very much relied on mechanical movements for most of its models. It will take until 1975 before Zenith was able to create its own. Dreadfully around that point, the instruction from its Chicago-based owner was issued: No more mechanical watches.

Rebel with a cause

Charles Vermot was part of the team from the Martel Watch Co., which Zenith acquired years ago, and was instrumental in the development and production of the El Primero movement. He continually wrote to Zenith’s American owners to plead the case for the continued production of mechanical watches yet received no response. The 1975 instruction to liquidate everything related to mechanical movement production initially struck fear to the head foreman in the ebauches department.

Yet from that initial shock, steely determination quickly followed. True to his convictions that the El Primero movement is a treasure that should be preserved, Charles Vermot hatched a plan. He started meticulously cataloguing the tools, components and plans vital to the production of this high-beat automatic chronograph movement as the site in Ponts-de-Marte was closed and eventually sold off.

Throughout a period of months, these vital articles were stored and hidden in plain sight in the attic of one of the buildings in the Le Locle complex. Charles Vermot would be helped by a very select few in this endeavour, albeit all the while being reminded that this was a fool’s errand. The head engineer’s will, however, never wavered. As the entrance to the room was bricked up and sealed, the El Primero may have been entombed but was safe from being lost to history.

A Legend Reborn

In 1980, Ebel emerged as one of the few survivors that started seeing a renaissance in its mechanical offerings. To develop a mechanical chronograph, it needed a solid movement and the world thought one of the best options may have been lost. Zenith, now back in Swiss ownership since 1978 under Paul Castella & Dixi, had a number El Primero movements that it agreed to sell to Ebel. Part of the treasure trove that Charles Vermot preserved all through those years, the El Primero saw the light of day in 1982 within Ebel’s 1911 Chronograph.

This caught the attention of Rolex which wanted to update the Cosmograph Daytona with a self-winding movement. Zenith needed to find a way to restart production to win the deal. Thanks to the actions of one Charles Vermot, it was able to resume production without having to take too much time, and more importantly, the required investment had it needed to start from scratch. In 1988, the Daytona ref. 16520 was unveiled powered by an El Primero-based movement. It would continue to power this piece until the year 2000, helping secure Zenith’s revival.

Frozen in Time

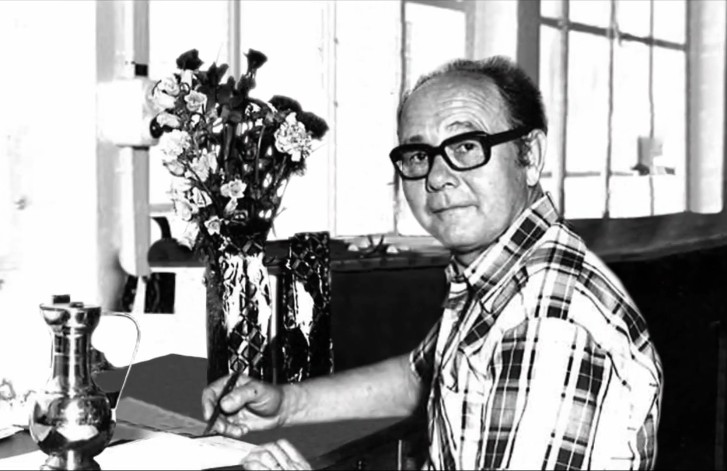

Reaching the doors of the attic, I felt being frozen in time. The place was largely left as it was all those years ago. The first section of the floor has an old-style television installed that shows sections of an interview of Charles Vermot as part of a feature by the Swiss channel RTS aired in 1991 (“Le retour du tic tac” – The return of the ticking clock).

There, in his own words, Charles Vermot talks of his shock when he got told that all mechanical watchmaking was to be ceased at Zenith, and all tools to be disposed of. He also describes the steps he took to start preserving the El Primero when his request to keep a small mechanical team going went unheeded. It even features a scene where he ascends the same steps that he took all those years ago holding the some of the tools that would later be used to resume production.

Perhaps the most moving part was when he recounts the moment when his actions were vindicated, by being asked to assist with the reproduction of the El Primero when he showed the parts, plans and tools that he stored in Le Locle. You can definitely tell the weight it bore on him and perhaps pride in having a hand in reviving a celebrated movement and in turn Zenith itself.

Further down the floor, we get to the section where all the El Primero tools, plans & components were hidden. Mixed in with the rest, you can see how the careful cataloguing by Vermot ensured it was both hidden but discoverable when the time is right. This section is probably where it hits you. The sombre lighting that was brought in by the few windows adds to the air of history. To think at how he went about putting the things those vital articles away in these shelves was both fascinating and sobering, as you walk over the wooden floors, and scan through the area.

There goes my hero

Charles Vermot is perhaps the hero that horology needed but did not deserve. Some might say what he did may have been a gamble, but what it showed is a dogged belief in the first high-beat self-winding chronograph movement being still relevant in the future. Unheeded but in the end, the man was vindicated.

Some might say the El Primero is but a trinket, pieces of metal held together to tell time. To others, it’s the life’s work of many engineers and craftspeople. An application of one’s skills and time in the pursuit of excellence in engineering and craftmanship. To be the first, and for that legacy to endure. The El Primero powered chronographs of modern times perhaps may not be as ubiquitous as some of its contemporaries, however, its legendary status is very much secured in horology lore.

Today, the building that houses the “attic” features a museum chronicling Zenith’s journey as a watchmaker from the early days, to the modern times. a collection covering marine chronometers, award winning pieces and even early examples of the legendary Calibre 135. Amongst the exhibits is an area dedicated to the man who saved the legendary movement. As you walk along a hallway that chronicles the journey of the movement from inception, slumber and revival on the right, you are flanked by equipment and models produced since, on the left. This all leads towards an exhibition honouring the man himself.

His desk with plans, a stamp and a photograph of his, presumably taken at Martel, welcomes you before heading up the stairs towards the grenier. Also on show is his daily wear, a Zenith Chronomaster A384 alongside the watch that was given to him by Zenith, an Academy Triple Calendar, in recognition for his pivotal role in reviving the El Primero in the 80s.

Finally, emblazoned on the wall, an extract of one of his letters to the then Chicago-based owners goes (translated to English):

Without being against progress, I observe that the world is such that there are always setbacks. You are wrong to believe in the complete demise of the mechanical chronometer. Furthermore, I am convinced that one day, your company will be able to benefit from the fashions and trends that the world has always known.

If your French is non-existent as mine, I would very much recommend you check out this article by grail-watch.com which has been very influential in the completion of this article. It features an English transcription of the RTS episode aforementioned. Also check out this article by Goldammer for an overview of the Swiss quartz pieces that came out in the 70s, with most being part of the Beta 21 consortium.

Leave a Reply